English Dept. Works to Diversify Curriculum

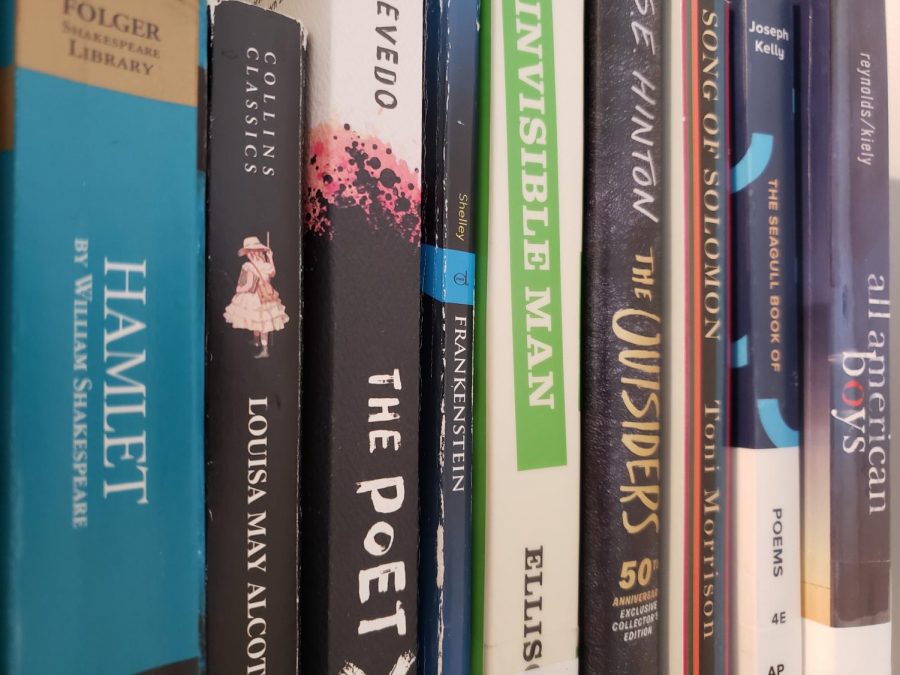

Old, dead, and ninety percent white. These adjectives often describe the composition of books, plays, and documents by authors like Mark Twain, Harper Lee, Shakespeare, and Thomas Jefferson.

Chelsea High School’s English department uses many of these authors’ works to teach curriculum standards, such as reading comprehension, text analysis, and text citation as well as using them for their social and moral lessons. However, using literature written by white, cisgender, and heterosexual authors with similar main characters does not allow for a diversity of experience or point of view. The English department knows this and is working continuously to repair.

“I think what was really important to us was bringing in minority voices and getting rid of as many dead white men as possible,” Chelsea English teacher Valerie Johnson said. “Having different perspectives for the kids, especially because we are predominantly white school, is incredibly important.”

After a curriculum review in 2018, the Chelsea English department has been making large shifts in their curriculum as well as re-selecting the literature that students read to increase the amount of diverse literature in Chelsea schools.

“When we first started looking at our curriculum we set up non-negotiables,” head of the Chelsea English department Dawn Putnam said. “Having multiple voices in our new curriculum and being representative of all—old and new, men and women, the privileged and the disenfranchised—was and is a top priority for us.”

It does appear that the department’s curriculum is becoming inclusive. Where juniors used to read books like Huckleberry Finn and The Crucible, they now read “Black Men and Public Space,” August Wilson’s play Fences, and have options like “Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe.”

In addition to changing what students are reading, the English department is re-thinking how they teach classics like Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), which discusses a lawyer’s battle with social norms and racism in the southern United States.

“I think that when I first started teaching To Kill Mockingbird, I was more inclined to look at all the good takeaways,” Putnam said. “We should be kind to people, we should use our privilege for good, Atticus Finch and what a great role model he is, and it is not that he isn’t in a lot of ways, but also there are a lot of problems with the book as well. Our current effort in teaching this novel focuses on understanding it within the context of when it was written and also considering it within the perspective of what it now means to be anti-racist.”

And for the most part, the changes in the Chelsea curriculum haven’t gone unnoticed. Sometimes, it’s not about changing the authors themselves, but rather shifting the focus.

“[Chelsea] doesn’t have the most diverse literature, but we’ve definitely gotten better,” Shawna Chester (‘22) said. “Diversity is not just about race or sex. It also includes socio-economic backgrounds and previous experiences. For example, Shakespeare was someone who lived in England, writing and putting in plays, changing how the public saw theatre. Harper Lee was someone who grew up in America, seeing these difficult scenarios involving racism and chose to enlighten the world about it.”

But despite all the positive changes implemented into the Chelsea curriculum, the seismic shifts that need to happen are not coming about as swift and easy as many have hoped, especially when it comes down to the larger book assignments.

“As far as To Kill a Mockingbird, some of its commentary on race is outdated,” Stella Moore (‘22) said. “Also, all the books we read are about and written by white people. Some teachers do a good job of adding supplementary reading from and about people of color, but that literature is never really the focus in the way that books like To Kill a Mockingbird are.”

And as far as progress goes, Chelsea’s has perhaps been relatively quick compared to other schools, but there’s still a ways to go when it comes to diverse literature.

“I think there will always be room for improvement,” Chelsea English teacher Amanda Knop said. “We’ve had these conversations as an English department, and we are willing to change more of the texts when we start to look at the curriculum again.”

The hope is that educators will be able to find alternatives to the older, more outdated texts and include more voices in the curriculum like authors of color and writers from the LGBTQ+ community.

“My hope is that, in the future, I’m not sitting here struggling to find a nature poem by a Japanese poet,” Putnam said. “We have enough resources now that we don’t have to be tied to what a textbook company gives us.”

Jasmine is a senior at CHS and this is her third year writing and editing for The Bleu Print. When she’s not correcting people’s grammar, Jasmine enjoys...